On the Hard Wood with John Edgar Wideman

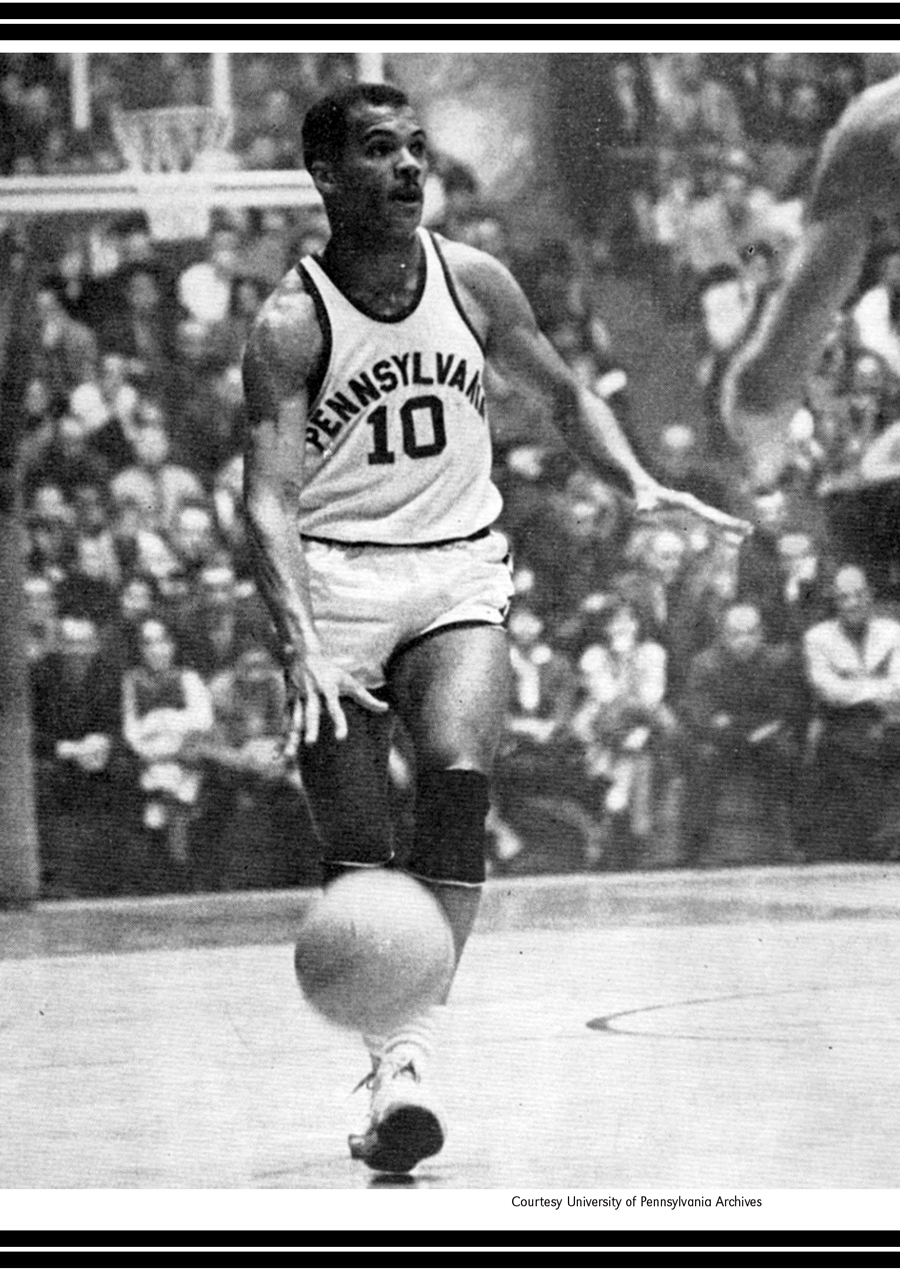

Basketball has deep roots in John Edgar Wideman's life. As an All-Ivy star at the University of Pennsylvania in the early '60s, Wideman drew on the street games of his youth, just as he would later as the only writer to win the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction twice. While Hoop Roots might be his book most directly inspired by the sport, his soon-to-be released collection Briefs could prove to be his most revealing. In Briefs, Wideman explores new literary territory—the short-short—even as he introduces a potentially game-changing move to the publishing world. With the aid of his son, Wideman is publishing his latest book in DIY fashion, using the internet-based Lulu to make it available on an indie basis. Not only will this give Wideman the opportunity to keep costs down for the reader, it will allow him to retain greater control over the book's contents and profits. Our scrappy little point guard Steven Lee Beeber goes one-on-one with this literary giant.

conduit: I want to start by looking at your upcoming collection, Briefs. In the piece, "Short Story," a jogger carefully sips from his water bottle only to recall that, as a child, he'd gulp lemonade too fast after playing basketball so that he'd cramp. This leads him—or perhaps I should say, you—to make a connection between the short-shorts in Briefs and the possibility that you've learned not to take on too much as a writer. Can you elaborate on this?

john edgar wideman: If the story works well, or the way I wanted it to work, it doesn't solve the problem. It's not a confession that the old gray mare ain't what it used to be. I don't want it to be that. I want to make the point—if there's such a thing as making a point, a single point with a story—that deciding to take on a story—long or short—is quite problematic. That is, when one is putting together a story or wanting to express something, that the urges are mixed. The motivation is always mixed; it's not about writing less as one ages. Some of the forces that are at play when one is 35 are still at play when one is 65. The forces are at play whether you're writing a 500-word story or are in the middle of a novel of indeterminate length. The signals are not always clear in life. You may think you're engaged in one kind of project only to get excited or forgetful or encouraged or inspired, so that it becomes another kind of project. You're not quite sure. And that's part of the magical business of composition and starting out on a road whose destination you're not altogether sure of.

conduit: In that same story, you note that playing basketball is a kind of existential act. "We were nothing, all players nothing, no name, no rep, everything to prove one more time, nobody 'til the game's rolling, your legs and heart pumping." If writing and athletics are related, as they seem to be throughout Briefs, do you also see writing as an act of self-definition?

wideman: It's an opportunity to show oneself and the game and also the people who are in the game or watching the game, where you're coming from, what you're trying to do, who you are. Yes, it's a way of establishing an identity, not once and for all, but it's part of a process for establishing an identity, an identity that never becomes fixed or finished, but is, in a weird way, a kind of flow of all the sorts of similar experiences before and after. It's a lot like putting together a life in general. You do things for the moment. You do things as a response to somebody or some pressure or some whim. But those little bits and pieces of experience are not unconnected to a bigger picture, although one is often quite unaware at the moment of what the big picture might be.

conduit: In "Genocide," another story that we're publishing in this issue, the narrator admires another, younger player's talent to such a degree that he wants to destroy that player so that he never has to see him go downhill. Considering the title, do you see competitive sports as a way of creating a projection of oneself, an "other" that you can then destroy?

wideman: The title, "Genocide," pushes that story outside the boundaries of the court, but it also suggests that inside the boundaries of the court all those larger emotions are at play and that they may be rooted there and in individual actions and one-on-one reactions. In other words, genocide is a natural outgrowth of the instincts inside oneself, which are self-protective and self-destructive and extremely powerful, extremely unsettling. Yes, I think, in a way, you see another player or you see another person, and in that person, you can see the return of the repressed, maybe something awful you've done to someone or something awful they've done to you. And for that moment, that player symbolizes it. And their very appearance sets up a very complicated and sometimes paradoxical, contradictory field of forces, of emotions.

Such moments definitely happen in basketball. It can be part of the psyche in each player. But at the same time, there's the counteracting force of the love of the game. If you really love the game, there is a kind of bowing down to it and concession to it that can create self-obliteration and self-annihilation. You do things to make the game better, to keep the game going. And you forget your own identity. You forget your statistics and you forget whether you make the shot or somebody else makes the shot. And that's part of what makes the game fun, makes it larger than life. But in terms of ego, in terms of identity, it's also threatening. It's threatening and the game can consume one to such a degree that it's scary. I guess that's true about any passion. So yes, watching a game, watching another player is somewhat like responding to a very powerful lover.

conduit: It's interesting that you use the term "one-on-one" to describe both genocide and the process of losing oneself to the game, especially seeing as another piece in Briefs employs that term as its title. In "One on One," a man who loves the game goes to a decrepit court where the net is constantly being ripped off due to players showboating, and he replaces the net only to promise that he will shoot, or at least frighten, the next person who damages it.

wideman: He wants to save the court.

conduit: To save the court, right.

wideman: To save the net.

conduit: Right. And when he actually does it, or tries to do it, the player in question sees the gun and grabs it, shooting him dead

wideman: Yeah. It's a good segue from what we've just been talking about. Because what happens, you've got two lovers of the game who, because of the game, become pitched enemies. And one is trying to do something good for the game and the other just wants to play the game, has no idea that this person who kind of appears as an enemy is really his friend. And so there's the ambivalence there, the inborn ambivalence. You never know what anybody else is thinking. You never know what's in somebody else's mind. You make assumptions and the arbitrary rules of the game kind of regulate those assumptions or create a context for those assumptions. But you're still stuck with the unpredictable, the unknown, always. And it can lead to something great, you know, playing ball with strangers and having a really good time, or it can lead to tremendous frustration, anger, even though the game may have started out as something that you both wanted to play and were dependent on each other for.

The latter is true for my guy who runs around trying to fix up the basketball courts—he's a little fucked up. He's like a lot of us, getting the symptom and the people who are afflicted by the symptom confused. So he's willing to either scare the crap out of somebody or hurt somebody who is as much a victim of the defacing or the destruction of the court as he, the avenger, is. As a result, people who should be on the same team become part of different teams.

conduit: As a kind of flipside to that, I remember an interview that appeared after the publication of Hoop Roots, your meditation on basketball. In it, you compared basketball to jazz, saying that both were improvisational African-American creations that allowed each player to have a part that's unique, and yet to also work as a member of a group.

wideman: Collaboration and improvisation are nice ideas, but they don't guarantee results. And there's just a tremendous amount of energy being focused on both those activities when both those activities occur. And it's a way of growing. It's a way to become larger than yourself and grow in the moment and grow over time. But you can also get pushed out. Your particular tone, your particular contribution can get minimized or overshadowed or ridiculed. And that can be part of the improvisation also, and the collaboration. So it's about intentions and it's about fate and who you happen to bump into and when you happen to bump into them. There are no rules. Just like there are no rules which produce art, there are no rules about collaboration and improvisation that make it necessarily positive.

conduit: So even though both jazz and basketball involve interplay between the individual and community, it doesn't mean that the relationship is always a positive one. That reminds me of a piece you wrote about your daughter, Jamila, when she was playing in the WNBA. In that piece, you noted that she and the other women in the league were conscious of their responsibility to their young female fans, whereas a player like Charles Barkley regularly protested that he didn't have to be a role model.

wideman: It's funny that you mention Charles Barkley. I don't know Charles, but he seems quite content to play a role in order to gain an income as an announcer, as a provocateur, sometimes as a clown in sports. He seems quite able to be dedicated to that role.

Of course, even as he says he's not a role model and shouldn't have to make some great statement, he is by definition making one. It's like some writers who say they're not political or don't want to do political writing. The very fact that they're trying to keep politics out of their work is a political statement of a different sort.

conduit: Do you think that's unfortunate in either the player's or the writer's case?

wideman: No, that's just how it is. It's really dangerous to make sweeping statements because the identity or the role that you're refusing can also lead to a trap. If you're in a society that's very good at confining and pinning and incarcerating people into one-dimensional roles, you may find that if you escape one trap, there will be another one waiting next door.

conduit: In another story from Briefs that we're publishing, "To Barry Bonds: Home Run King," the narrator seems to protest against the way our culture has imprisoned Bonds in the bad boy role. He recalls that as a young player, he too pushed his body to the limits, yet he implies that in doing so he almost lost his identity.

wideman: Well, in order to play the game of that story, it takes both the narrator's experience and the narrator's admiration of Bonds. The story suggests Bonds (and the narrator's) willingness to be ruthless with both others and himself, whether in terms of body, mind, morals, or whatever. It's not all spelled out, but I think the narrator believes that's the price. He believes that if you want to be extraordinarily good at something, there's no way of avoiding the extreme price of that achievement. The narrator is identifying with Bonds on those grounds. In other words, he's also not being holier than thou, not preaching at Bonds.

conduit: The story that immediately follows "To Barry Bonds: Home Run King" picks up these same themes, especially the idea that by escaping one identity we often become trapped in another. In "Northstar" a man convinces his girlfriend to have anal sex, and imagines when they cross that taboo line he'll feel like a fugitive slave following the North Star to freedom.

wideman: He thought he would feel that way. He thought that freedom would be this kind of scary exhilaration. But at the same moment, he finds it's also kind of a scary, lonely, end of the world sensation as well, like, "Here I am. Well, this is what I asked for. And I'm out here, but whoa, where is here?" It's the loneliness at the top, which is the loneliness of a Bonds, the loneliness of a baseball player who's at the top. And, you know, anything can happen when you get there. It might be the best feeling in the world. It might be the beginning of falling down again, going back down again and losing it. So it's something like that.

conduit: There also seems to be a preoccupation in both stories with viscera and the body's softer, more vulnerable aspects, all the gooey, internal parts that can be hurt.

wideman: Well, the humiliations of the flesh are particularly acute when you've honed your body to the point where you can expect wonderful things from it, and then you find that it also stinks and has secretions and muscle pulls and that, like any machine, it breaks down. The body is not always fine-tuned and it can get in the way, and it's beyond one's control, even if you are a star, or you've managed to achieve the status of a star.

Many of these stories, the little stories, the briefs collectively, are about big moments in an individual person's life. But for me, they're also metaphors about our national life, about our national character, about our history. So a story like "Genocide," which is about a basketball player, in my mind is also about slavery. It's also about the ambivalence of Europeans confronting Africans and being kind of fascinated by these different looking people who had a different society and spoke different languages and how that fascination, that attraction, ultimately became a reason for abuse and murder and Apartheid, etc. And if you're thinking about something, some adventure of anal sex because it, you know, breaks the norm and seems very attractive, it can also wind up to be something else indeed. It can be a point of misunderstanding. The characters in that story are trying to please one another, but their timing is bad. And they very possibly create space, a barrier that will never be surmounted between them. It's like the process and history of integration in America. That well-intentioned attempt on some people's parts to bring the quote-unquote "races together," may also be the very exercise, equally well-intentioned, that makes it impossible for people to really get rid of their differences.